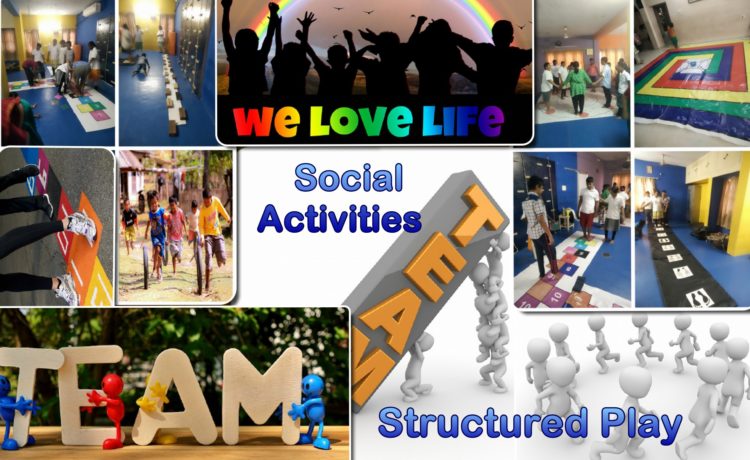

Social Activities Structured play

Social Activities Structured play

Structured play can be a good way for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to learn play skills like sharing, taking turns and being with other children.

How autism spectrum disorder can affect play

Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) enjoy playing, but they can find some types of play difficult. It’s common for them to have very limited play, play with only a few toys, or play in a repetitive way. For example, your child might like spinning the wheels on a car and watching the wheels rotate, or might do a puzzle in the same order every time.

Because ASD affects the development of social skills and communication skills, it can also affect the development of important skills needed for play, like the ability to:

- copy simple actions

- explore the environment

- share objects and attention with others

- imagine what other children are thinking and feeling

- respond to others

- Take turns.

How structured play can help children with autism spectrum disorder

Structured play is when a grown-up provides resources, starts play or joins in with children’s play to offer some direction or guidelines. Free play is unplanned play that just happens, depending on what children are interested in at the time. Both are both important for children’s development, but structured play activities are particularly useful for children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) who are learning early play skills like sharing, taking turns and interacting with other children.

This is because a structured play activity usually gives children clear guidelines about what to do and when. It also usually has a clear end point. This reduces the number of options that can come up in a play scenario, which can sometimes be overwhelming for children with ASD. A clear structure can also help your child understand the steps, skills, activities or ideas that are needed to get to the end goal of the game.

All of this creates a lower-stress environment where your child can practice the skills he needs both to play and interact successfully with other children. Once your child has learned the steps, over time she might be able to start and finish the activity without support.

How to structure a play activity for children with autism spectrum disorder

The first step is choosing an appropriate play activity. Activities that have a clear goal and ending are best, like jigsaws, puzzle books, song and action DVDs, picture lotto and matching games.

Next, you could try creating a visual schedule:

-

- Represent each step of the activity with visual cues attached to a board. The cues could be objects, pictures or words.

- Pull off each cue during the activity as your child progresses, so that you clearly show what the next stage of the activity is.

- Gradually reduce your support until your child can use the schedule and complete the activity on his own.

To start with, your child might not find the activity or its end result fun by itself. You might need to add something else to help your child learn that this type of play can be fun. For example, if your child loves your tickles, you can tickle her after each stage of the activity is finished, and then have a big tickle session at the end of the whole activity. This extra reinforcement will help your child to have a positive experience of the structured play activity while he’s still learning play skills.

Top tips for structured play with children with autism spectrum disorder

These tips can help you and your child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) gets the most out of structured play:

- Use your child’s interests. For example, if your child loves Thomas the Tank Engine, start by using Thomas-themed jigsaws, puzzles or colouring books.

- Choose activities that your child can do. Think about what stage your child is at and try moving play onto the next stage. For example, if she’s banging blocks, introduce some turn-taking with the blocks

- Use your child’s strengths. For example, if your child responds well to visual cues, try a very visual activity like sorting coloured blocks.

- Talk only as much as you need to.

- Keep playtime short.

- Redirect inappropriate play. For example, if your child is banging blocks together, you could prompt him to stack them, or redirect him to an activity that involves banging.

Developing Play

As your child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) becomes more able to complete structured play activities on her own, you can begin to expand how long you play and the number of activities you do with your child. For example, once your child can complete a few activities, try to set up a few different play stations around the house. This way, your child can practice moving between activities and focusing on different things without having you there all the time.

Structured play groups help students develop their play and social engagement skills. They involve carefully chosen play activities which encourage peer interaction and build social and communication skills. The groups normally include a balance of students with social support needs and typically developing peers who can act as models. Activities and materials used are carefully selected to foster interactive play and skill building is supported by teachers and other adults.

How do I use it?

- Identify no more than two students with social support needs.

- Select two or three peers who are good at socialising, are helpful to others and able to follow adult direction well.

- Identify no more than two goals for the group e.g. the student will learn turn-taking while interacting with peers in a fun activity

- Select activities for the group e.g. construction or dramatic play activities that match the interests of the students

- Collect the necessary materials for the activity

- The play session should last no longer than 30 minutes.

- Implement the play group at appropriate times e.g. during whole class free play or group activity times. The adult/teacher helps scaffold the play, offering advice or direction when needed.

Getting Started (Activity or Event)

What important events or activities tend to set up the behaviour?

When the individual experiences or is engaged in one of the following:

- Is in the community

Out on an excursion with the school, out shopping, attending a club, playing or attending a sporting activity - Has recently been disciplined

Has been reprimanded for an action or behaviour, has had something important confiscated as a consequence of an action or behaviour. - Is engaged in an activity or task they dislike

Has been asked to complete a non-preferred task or activity. - Is eating

- Is working in a group

Small group Maths or English lesson, social skills group, unmonitored small group learning such as independent reading groups. - Is working independently

Has been asked to complete a task on their own without assistance. - Is in a regular class

Is working with the rest of the class in the classroom in a standard lesson (e.g. Maths, English) - Is playing

Is playing inside or outside during a scheduled break, is engaged in free time in class, this could be structured or unstructured, alone or with others. - Is returning to school after a break

Has returned after a holiday or a public holiday, after being sick, after a suspension. - Has had a change in routine

Has a relative visiting, has a relief/ new teacher, doctor/ dentist appointment. - Is attending a special event

At school- Sports Day, Anzac Day Parade, and incursion. At home- a friend’s birthday, a sporting event. - Is in a specialist lesson

Music, PE and Art - Is transitioning between activities or settings

Transitioning can refer to moving from one classroom to another, one classroom activity to another or from an activity to playtime or lunch. It can also refer to moving from the playground to lining up or getting out of the car to go into the classroom. Therefore a transition is any moment in time where the individual is required to move from one area or activity to another. It is important to recognise that some people may be more or less sensitive to the changes between activities, locations or people, so although you may feel that the change was minimal (e.g. moving from working on their desk in the class to working on a desk in the library), this may feel more significant to somebody else. Other examples include moving between classes, from class to lunch, home to school, home to job or starting a new class or school year. - Is unwell or tired

This may be identified by the individual or others who know them.

What happens before

What happens to set off the problem behaviour? Often it’s when someone..

- Directs them to start or continue with a disliked task

Directs individual to start or continue with a non-preferred task or something that the individual finds difficult or uncomfortable. - Directs them to stop a liked task

Asks them to stop an enjoyable activity or task. - Does not respond to their approach

Individual does not respond to another person’s approach and continues with the behaviour or activity e.g. does not notice them trying to gain attention, does not stop talking to another person when approached. - Does not respond to their request

Individual does not respond to another person’s request e.g. does not answer a question or join in with an activity - Gives a physical prompt

Individual is given a physical guide to complete a task or reengage with an activity e.g. touches person, or taps them on their arm or shoulder to gain their attention or guides their hand towards the task. - Gives a verbal direction or request

Somebody says a direction or request to the individual. This may be directly to the individual or to a group of people. - Gives verbal praise

Verbally praises the person for something, either about the person themselves or something they have said or done e.g. “good job” or “you did really well in that sport lesson”. This may be directly to the individual or to the whole class. - Gives a verbal reminder

Somebody reminds the individual of something by saying it to them e.g. “it’s time to get in the car”, “go back to class”, “brush your teeth”, “don’t forget to pack your lunch”. This may be directly to the individual or to a group of people. - Gives a verbal reprimand

Tells individual off, possibly for doing something or saying something . - Makes an unexpected noise or sound

Person or people nearby make sudden noise or sound such as a hand clap or shouting . - Moves away

Moves away from the person intentionally or unintentionally. - Moves closer

Moves closer to the person intentionally or unintentionally - Refuses a request

Refuses to do something or let the person do something

What happens after

What happens as a result of the individual engaging in this behaviour?

The individual is then:

- Given a verbal redirection to stop the behaviour

The individual is given a spoken instruction which has the aim of stopping the behaviour and directing them towards a more acceptable behaviour e.g. “Chairs are for sitting. No standing please” . - Given more information or clarification of the direction or request

Clarify and simplify the expected task. Break it into one or two steps at a time. Make the directions explicit. - Allowed to remain with preferred task or activity

Is allowed to continue with the an activity or task they enjoy or would chose. - Reminded of the rules and consequences

Is reminded of house, school or workplace rules and the consequences that follow if the rules are broken. - Asked the Responsible Thinking Questions

Responsible thinking questions allow the individual to make choices about their actions. E.g. What are you doing? What are the expectations? What happens when you ignore these expectations? Is this your goal? What do you want to do now? - Given a forced choice

Instead of telling the individual what to do, options are presented as a choice e.g. “do you want to do your Maths or English homework?” or “If you don’t complete this activity now you are choosing to finish it at break time” - Ignored

Others do not respond to the behaviour, either purposefully or not. - Given attention by peers

Peers watch on, join in or encourage the behaviour (this may be positive or negative attention). - Given 1:1 attention from adult

An adult directs their attention to the individual exhibiting the behaviour. This may be positive or negative attention, and would include things like speaking to the individual to tell them that their behaviour is wrong or sitting with the individual to encourage them to complete a task. - Given reduced task demands

Individual is given a section of the task to complete instead of all of the task. - Redirected to a different task or activity

Individual is directed to a different task. - Isolated

Individual is removed from the area where the behaviour has occurred or the people around the individual are removed from the area. - Sent to another area

Individual is directed away from the location they were when the behaviour occurred, this would include being sent out of the class or to a safe zone.

Problem Behaviour

What does the problem behaviour look like?

The individual:

- Is off task but remains seated in appropriate area

Is not participating in the requested task but is not moving around the room. - Is off task and distracting other students

Is not participating in the requested task and is disturbing others by moving around or being noisy - Does not respond to direction or request

Will not follow directions. Ignores requests. - Leaves their seat without permission

Gets up and moves around the room they are in when it may not be appropriate. - Makes repetitive requests or sounds

Repeats questions or sounds, may be distracting for those around. - Verbally refuses or rejects directions or request

This may be with words (e.g. “no”, “go away” or other sounds in response to being asked to follow a direction. - Becomes verbally abusive

This may be noises, single words or phrases e.g. shouting or swearing. - Becomes physically aggressive

Becomes physically aggressive towards the person or people around them e.g. hits, bites, throws objects, moves furniture or physically attacks another person. - Destroys property

Breaks or damages property around them (this may include their own possessions or ripping up pieces of work).

Desired Behaviour

What do you want to see them doing instead?

- Follow the direction

Individual follows the direction given and participates in the activity requested. - Start task

Individual starts or attempts task after a suitable amount of take up time. - Stop task

Individual stops the task. - Acknowledge the reminder

Verbally or non-verbally acknowledge that they have been given a reminder - Acknowledges the praise

Individual acknowledges the praise verbally or non-verbally. - Work quietly

Work quietly without distracting others individuals from their own work - Tolerate light brief touch

Individual is able to accept a light brief touch, which may be for a redirection, reminder or attention getter or may be due to somebody witting in the close vicinity. - Ask person to move away or closer

Individual is able to verbally or non- verbally request that a person moves closer to them or away from them. - Ask for help

Individual is able to ask another person for assistance verbally or non-verbally. - Ignores interruption or noise

Individual continues to work without reacting to interruption or noise. - Repeats request or question

Individual repeats the request or question for clarification. - Accepts refusal

Individual accepts that their request cannot be fulfilled, e.g. not allowed access to an activity or object they have requested.

Consequence

What will happen when the individual displays the desired behaviour?

- Provide tailored adult attention

Give the individual some specific adult attention e.g. some positive feedback. - Given additional time of preferred activity

Individual is given some extra time on their preferred activity after the task is complete. - Verbal acknowledgement of compliance or success

Praise or positive feedback. This may need to be done without anyone around the individual hearing. - Assign free time or choice of preferred activity

Give individual a designated amount of time later in the day to engage in a preferred activity. - Offer choice of tasks or scheduling of tasks

Give the individual a limited amount of predesignated choices of activity, or allow them to choose when they have to complete the task

Acceptable Alternative

What behaviour would you accept as an alternative while teaching the desired behaviour?

- Ask for help

Lets someone know that they require help (verbally or non-verbally). - Tell adult they are uncomfortable

Lets an adult know they are feeling uncomfortable (verbally or non-verbally). - Politely decline

Lets the other person know that they do not want to join in the new activity. - Accepts the reminder

Individual accepts the reminder and moves to the task after a period of take up time. - Go to pre-arranged safe space

Moves to pre-arranged safe zone such as a tent or quiet corner in the classroom, support room or buddy class. At home, this may be their bedroom. - Works on alternative task

Works on a task other than the one set, which may or may not be related to the initial task assigned. This may be one the individual has identified or may be one set by the adult. - Waits quietly for assistance

Waits without interrupting other individuals. Possibly engaged in pre-arranged quiet activity.

What is the function, or reason, for the behaviour?

People engage in millions of different behaviors’ each day, but the purpose or “functions” of these different behaviors’ tend to fall into the categories listed below. Remember: once the function has been met the problem behavior should stop. If it doesn’t stop then you haven’t identified the correct function and you will need to revisit the information you have entered. This is a good result – the more functions you rule out the closer you will get to the true function.

These functions are to either get access to, or to stop/avoid:

- Stimulation or sensation: This could be escaping from a sensation that is unpleasant (such as a noisy hall or flickering light) or accessing something that is enjoyable. Remember, everybody has different sensory preferences, so what is normal or enjoyable for one person may be uncomfortable or distressing for another.

- An item or activity: This could be escaping or avoiding an activity or task that is difficult or not enjoyable, or gaining access to a favourite or preferred item or activity (e.g. access to technology).

- Social situation with child: This could be any behaviour to get or stop focused attention from siblings, peers, or other children that are around them. Remember, whilst some individuals find attention from other children positive, others will find it unpleasant and will therefore show behaviours to try and make it stop.

- Social situation with adult: This could be any behaviour to get or stop focused attention from parents, teachers or other people that are around them. Remember, being disciplined and told-off might sometimes be a form of gaining engagement from adults.

With this information in mind, take some time to look through the diagram that you have completed and think about what changed as a result of the behavior. Remember, use the information in the diagram to inform you; sometimes the function of behaviors’ can surprise people!

ABA-Applied Behaviour Analysis

ABA-Applied Behaviour Analysis

ABA-Applied Behaviour Analysis

Behavior analysis is a scientifically validated approach to understanding behavior and how it is affected by the environment. In this context, “behavior” refers to actions and skills. “Environment” includes any influence – physical or social – that might change or be changed by one’s behavior.

On a practical level, the principles and methods of behavior analysis have helped many different kinds of learners acquire many different skills.

What is Applied Behaviour Analysis?

Behavior analysis focuses on the principles that explain how learning takes place. Positive reinforcement is one such principle. When a behavior is followed by some sort of reward, the behavior is more likely to be repeated. Through decades of research, the field of behavior analysis has developed many techniques for increasing useful behaviors and reducing those that may cause harm or interfere with learning.

Behavior analysis focuses on the principles that explain how learning takes place. Positive reinforcement is one such principle. When a behavior is followed by some sort of reward, the behavior is more likely to be repeated. Through decades of research, the field of behavior analysis has developed many techniques for increasing useful behaviors and reducing those that may cause harm or interfere with learning.

Applied behavior analysis (ABA) is the use of these techniques and principles to bring about meaningful and positive change in behavior.

These techniques can be used in structured situations such as a classroom lesson as well as in “everyday” situations such as family dinnertime or the neighborhood playground. Some ABA therapy sessions involve one-on-one interaction between the behavior analyst and the participant. Group instruction can likewise prove useful.

How Does ABA Benefit Those with Autism?

Today, ABA is widely recognized as a safe and effective treatment for autism. In particular, ABA principles and techniques can foster basic skills such as looking, listening and imitating, as well as complex skills such as reading, conversing and understanding another person’s perspective.

Today, ABA is widely recognized as a safe and effective treatment for autism. In particular, ABA principles and techniques can foster basic skills such as looking, listening and imitating, as well as complex skills such as reading, conversing and understanding another person’s perspective.

That ABA techniques can produce improvements in communication, social relationships, play, self care, school and employment. These studies involved age groups ranging from preschoolers to adults. Results for all age groups showed that ABA increased participation in family and community activities.

A number of peer-reviewed studies have examined the potential benefits of combining multiple ABA techniques into comprehensive, individualized and intensive early intervention programs for children with autism. “Comprehensive” refers to interventions that address a full range of life skills, from communication and sociability to self-care and readiness for school. “Early intervention” refers to programs designed to begin before age 4. “Intensive” refers to programs that total 25 to 40 hours per week for 1 to 3 years.

These programs allow children to learn and practice skills in both structured and unstructured situations. The “intensity” of these programs may be particularly important to replicate the thousands of interactions that typical toddlers experience each day while interacting with their parents and peers.

Such studies have demonstrated that many children with autism experience significant improvements in learning, reasoning, communication and adaptability when they participate in high-quality ABA programs. Some preschoolers who participate in early intensive ABA for two or more years acquire sufficient skills to participate in regular classrooms with little or no additional support. Other children learn many important skills, but still need additional educational support to succeed in a classroom.

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy

COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a talking therapy that can help people to manage their problems by changing the way they think and behave.

CBT is designed to help people notice and understand how their thoughts, behaviors’ and emotions affect each other. It is also designed to help them learn new ways of thinking about and responding to distressing situations.

The therapist breaks down problems into feelings, thoughts and actions to work out which are unhelpful or unrealistic. The therapist then teaches the client how to replace those feelings, thoughts and actions with more helpful and realistic ones.

There are numerous interventions for people on the autism spectrums which are based on, or which incorporate, the principles of CBT.

These include multi-component CBT programmed such as Behavioral Interventions for Anxiety in Children with Autism; Exploring Feelings; and Facing Your Fears.

BEYOND BEHAVIOUR

Therapies based on the science of behavior have been effective for people of all ages, and are an essential item in any mental health professionals toolkit. They only go so far, however. Human beings are “meaning makers.” That is, their behavior is not just the result of stimulus and response or reward and punishment. They take in what is happening around them and give it meaning, loaded with emotion. Then they behave.

CBT takes into account the thoughts (or cognitions) we have about things, the feelings that result, and the behavior that follows.

CBT: A POWERFUL APPROACH

ADAPTING CBT FOR ASD

In recent years, there have been a number of attempts to adapt CBT for children and teens on the autism spectrum. The focus has often been on those who also have anxiety because this is so common in individuals with ASD.

One challenge was to find out whether children with ASD have the skills necessary to succeed at CBT. Fortunately, it appears they do. A study published in 2012 evaluated the cognitive skills of children with ASD and compared them to those of typical children. The children with ASD had the skills required for CBT in almost every instance. They were able to distinguish thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, and to work on altering their thoughts. Their only area of difficulty was in recognizing emotions.

In addition, traditional CBT tends to require strong linguistic and abstract thinking abilities, and these can be a challenge for individuals on the autism spectrum. Realizing this, researchers have worked to develop modifications to CBT that render it more ASD-friendly, such as making it more repetitive, as well as visual and concrete.

For example, instead of merely asking children to verbally rate their anxiety on a scale of 1 to 10, the therapist might have a thermometer showing anxiety from low to high and have the participants point to the prop to illustrate how high their anxiety is around a certain situation. Another strategy is to focus on the children’s talents and special interests, which helps keep them engaged and motivated, and to build in frequent movement breaks or sensory activities for those who might have problems with attention or sensory under- or over-reactivity.

For example, instead of merely asking children to verbally rate their anxiety on a scale of 1 to 10, the therapist might have a thermometer showing anxiety from low to high and have the participants point to the prop to illustrate how high their anxiety is around a certain situation. Another strategy is to focus on the children’s talents and special interests, which helps keep them engaged and motivated, and to build in frequent movement breaks or sensory activities for those who might have problems with attention or sensory under- or over-reactivity.

CBT can be delivered in a variety of ways: individual, family, group, or even family and group. The advantage of group CBT is that individuals with ASD learn that others are struggling with the same issues, and they begin to overcome them together. Friendships and social support gained through this process may be healing in themselves.

The advantage of family CBT is that it involves parents, educating them about their child’s challenges and teaching them to encourage use of CBT techniques when real life situations confront their child. This can make them feel more hopeful and confident in their ability to contribute to positive change in their child’s life.

However it recommended that CBT might be appropriate as a treatment for anxiety and depression in many adults on the autism spectrum, as this is in line with existing guidance for those disorders, provided those programmes are modified to meet their specific needs.

It also reported that there is insufficient evidence to determine if CBT is an effective treatment for other coexisting mental health disorders (such as depression) in children on the autism spectrum. However it recommended that CBT could be used for the treatment of those disorders in children on the autism spectrum, as this is in line with existing NICE guidance for those disorders.

Our Opinion

- There is a reasonable amount of high quality research evidence to suggest that multi-component CBT programmes may help reduce the symptoms of anxiety in some primary school children and adolescents on the autism spectrum who have an IQ of 70 or more.

- There is insufficient evidence to determine whether CBT programmes can help any child or adult on the autism spectrum with other issues, such as anger or depression.

- There is insufficient evidence to determine whether CBT programmes can help people with the core features of autism.

- There is insufficient evidence to determine whether CBT programmes can provide any benefit to adults on the autism spectrum.”

- Carrying out a detailed assessment of the individual, including any key strengths and weakness.

- Modifying the therapy to take account of the needs of that individual, including any strengths and weaknesses.

- Use of a longer assessment phase and an increased number of treatment sessions to help the initial engagement with the therapist, to enhance emotional literacy, and to practice, consolidate and generalise the techniques learnt.

- Using a range of appropriate measures to evaluate the effectiveness of the therapy.

Parental Counselling

Brain Gym Exercises

Psychological counselling for slow learner, parental guidance and counselling.

As parents, looking after ourselves is something that seems to get put way down the list of priorities. Everything and everyone are somehow organized, nurtured and sorted out irrespective of how we may be feeling. If life appears to be getting out of control or you’re not coping so well, don’t think you have to manage it alone. The old adage ‘a problem shared is a problem halved’ has truth in it, and there are plenty of professional services which can help you in a time of need.

School counselors

When there is an issue in some way related to school that is affecting the whole family, school counselors are a great place to go for help. School counselors are experienced teachers who have formal qualifications in counseling. They are available for all students from preschool to Year 12, and their families. As with any professional service, they will keep information confidential, unless child protection legislation overrides it or where someone may suffer serious harm from information being withheld.

Face-to-face support

Your doctor is a good person to approach initially for some advice or assistance if life is getting out of hand. If you need further support, your doctor can provide you with a referral to a psychologist or another other type of counselor. However, if you want to find a psychologist yourself.

What is Child Counseling?

Child counseling is a specialized area of psychology focused on working with children who have a mental illness, have experienced a traumatic event, or are facing a difficult family situation. Child counseling often deals with many of the same issues that adults do, such as anxiety or grief, but this type of therapy focuses on breaking these problems down so that children can understand and make sense of them.

Child counseling is a specialized area of psychology focused on working with children who have a mental illness, have experienced a traumatic event, or are facing a difficult family situation. Child counseling often deals with many of the same issues that adults do, such as anxiety or grief, but this type of therapy focuses on breaking these problems down so that children can understand and make sense of them.

Child counselors are specialists who can offer insight into the inner workings of your child’s development that are not necessarily visible to even those closest to the child. Most important of all, your child may not be able to tell you what sort of help they need, so your judgment is critical in ensuring your child receives the therapeutic intervention that is best for them.

Child Counseling can help kids interpret issues in a way that they can understand. Child counselors and therapists are highly trained in the thought processes of children so they can help kids and youths to interpret issues or trauma in a way that they can understand. When a child’s emotional issues are left untreated, it’s likely that they’ll impact the child’s educational and development and can also persist into adulthood.

Children of all ages can attend counseling sessions, from young preschoolers to teenagers. Every age within this range falls into the realm of child counseling until they are adults and no longer need children’s counseling techniques. Child counseling aims to help children work through their emotions so they can live normal healthy lives without fear, confusion, anxiety or trauma in their lives.

Why Seek Child Counseling?

When dealing with the mental and emotional health of your young child, sometimes the guidance of a professional can illuminate the underlying issues your child is experiencing. Many children are unable to express the complexities of having emotional or mental problems, so counseling can be an excellent option to explore the causes of your child’s issues.

In many cases, children who have a mental illness such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, or general anxiety disorder. Parents and physicians may seek the services of a child counselor to help determine a diagnosis, or counseling may be part of a key part of a treatment plan for mentally ill children. Child counseling unites your concerns with the knowledge of a therapist who has the tools and experience to help your child through difficult times. Parents want the best for their children, but the situation may be too challenging to handle on your own, especially as you are emotionally involved. When you seek child counseling, a third-party professional can help your child with strategies that are designed with their well-being in mind, first and foremost.

Issues Addressed by Child Counseling

If your child has experienced tragic or unsettling events in his or her life, such as the unexpected loss of a loved one or an abusive episode, the stress of the situation may be difficult for them to understand. Some of the most common issues that child counseling addresses are:

- Divorce

- Death of a loved one and grief

- Witnessing or experiencing a trauma

- Mental health diagnoses, including anxiety and depression

- Bullying

- Sexual, emotional, or physical abuse

- Relocating schools or cities

- Substance abuse or addiction in the family

Signs Your Child May Need Counseling

A child who displays developmental problems or acts out in ways that are beyond what’s considered normal can likely benefit from counseling, especially if there has been a recent trauma or significant event that impacts their lives, like a death or divorce. Some of the signs that your child is in distress and could need counseling include

- Unwarranted aggression

- Incontinence

- Difficulty adjusting to social situations

- Frequent nightmare and sleep difficulties

- Sudden drop in grades at school

- Persistent worry and anxiety

- Withdrawing from activities they normally enjoy

- Loss of appetite and dramatic weight loss

- Performing obsessive routines like hand washing

- Expressing thoughts of suicide

- Talking about voices they hear in their head

- Social isolation and wanting to be alone

- Alcohol or drug use

- Increased physical complaints despite a normal, healthy physician’s report

- Self-harm such as cutting

Goals of Child Counseling

Child counseling addresses major issues in a child’s life with the intended outcome being that they can learn tools to deal with stress or trauma. Some of the common goals of child counseling include being able to cope with difficult situations such as:

Anxiety:

Anxiety:

Children who attend counseling are encouraged to learn techniques to deal with emotional distress and anxiety on their own. Children can learn to prevent panic attacks or cope with anxiety in a variety of ways, which they will learn in their counseling sessions. Some strategies they will learn may include breathing exercises, changing negative self-talk, muscle relaxation, talking to a trusted adult about their feelings instead of keeping them inside, and asserting themselves by knowing when to remove themselves from a stressful situation. Teaching these techniques to children gives them a toolbox of coping mechanisms that they can use when they become anxious or experience a panic attack.

Trauma:

Unfortunately, some children experience traumatic events and are exposed to disturbing situations that they should not have to witness or be part of. After a trauma, a child may experience shock, disbelief, detachment or emotional numbness, fear, and may develop post-traumatic stress disorder. Symptoms of PTSD include strong desire to avoid the people or places where trauma was involved, vivid and distressing memories or flashbacks, nightmares or insomnia or fear of going to sleep, and being easily angered or agitated. Child counseling aims to help children talk about the trauma that they faced, rather than keeping their experiences and emotions inside. Many children who experience trauma develop trust issues and may have a difficulty finding the words to express their feelings and may blame themselves for what happened.

Child counseling teaches children that it’s okay to talk about their experiences and that they can use a variety of coping mechanisms. When a child has a flashback to their trauma, child counselors teach them tools such as deep breathing, seeking out an adult to talk to, relaxing their muscles, and correcting the misinterpretation of traumatic events.

Divorce:

When a marriage dissolves, it can be very challenging for children in the family to cope with. Many children blame themselves for their parents splitting up or have feelings that they are unloved. With divorce often comes changes in custody, and in some cases, there are tense custody battles between parents. Children can feel guilty about choosing which parent they want to live with and feel distress if their choices or feelings don’t align with their siblings. Child counseling teaches children to deal with feelings of sadness, fear, and guilt by giving them techniques to use such as deep breathing, journaling or art therapy, practicing positive self-talk, and talking about their feelings with their parents or another trusted adult.

Grief:

A death of a loved one, whether it’s a family member, peer, or friend of the family is distressing for anyone; however, children often cannot cope with death in the same way that adults can. For children, it may be difficult to understand their feelings of loss, despair, sadness, and missing the person who died. Often, children may have irrational thoughts such as the fear that they will also die, thinking that the death was their fault, or believing that they could have prevented it. Child counseling helps children understand the grieving process and teaches them that it’s okay to experience the emotions that arise after losing a loved one. Coping strategies may include being able to talk about their feelings, channeling grief through creative pursuits like journaling or art, and allowing themselves to speak or think about their loved one through sharing personal memories. Teaching children the stages of grief is another technique that helps them understand that how they feel is normal and natural.

Significant Change:

For many children, events, like moving to a new city or changing schools, can be stressful. Many adults can accept these changes as part of life, so you may not realize the impact it has on your child. Children who have difficulty dealing with change can experience feelings of insecurity, anxiety or worry, or anger towards their parents. While these are normal reactions to significant change, many children have a hard time moving past these feelings on their own. Child counseling teaches children to cope with change through learning to focus on the positive and stable aspects of their life, positive self-talk, deep breathing exercises when anxiety arises, and understanding that change is natural, understanding that their feelings are temporary and will fade when they adjust to the situation.

Self-Esteem and Confidence

Many children struggle with poor self-esteem and low confidence which can lead to depression, substance abuse, eating disorders, or thoughts of self-harm. When a child has poor self-esteem, they may feel unloved, worthless, and their friends and family would be better off without them. Child counseling can help children improve their self-esteem in a variety of ways, including digging deeper into underlying issues that may have caused these beliefs, recognizing negative self-talk and turning it into positive thoughts, using affirmations to gain confidence and self-acceptance, and talking to a trusted adult when troubling feelings arise. If a child’s low self-esteem has developed into something more serious, like an eating disorder, child counselors are equipped to help children overcome those issues.

Types of Child Counseling

Cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT):

CBT focuses on helping children change negative styles of thinking and behaving by correcting or re-purposing the thought process toward a more positive response. CBT challenges the automatic internal beliefs a child has about themselves and teaches them to view themselves and their situation through a more realistic and positive lens. CBT provides children with practical tools for coping with difficult or stressful situations that they can learn to use on their own.

Trauma-Focused CBT (TF-CBT):

TF-CBT is designed to help children overcome the effects of trauma. As with traditional CBT, children are taught to see events more realistically without blaming themselves. TF-CBT teaches children strategies that they can use when they experience a flashback so they can work through the memories from a place of control and understanding, and gives them the ability to use these tools on their own.

Alternative Therapies:

Children respond well to alternative types of therapies like art therapy, music therapy, movement therapy, equine therapy, mindfulness, or aquatic therapy.

What to Look for in a Child Counselor?

When seeking a counselor for your child there are several considerations to keep in mind. First and foremost, a child counselor must be a good fit for your child.

When seeking a counselor for your child there are several considerations to keep in mind. First and foremost, a child counselor must be a good fit for your child.  Chances are, your child will be uncomfortable with their initial counseling sessions, but it’s important that they work with a therapist that they are a good interpersonal match with. If your child is not comfortable with their counselor after several sessions, you may consider looking for another person who is a better personality fit for your child. Another important consideration is what the counselor’s training and qualifications are. It’s imperative to use a counselor who specializes in child counseling so they can apply therapy techniques to a young mind. Since you’re dealing with your child’s mental well-being, don’t hesitate to check references, credentials, and meet with a potential therapist to gauge your comfort level. Often therapists offer free consultations in which they can explain how beneficial counseling will be for your child

Chances are, your child will be uncomfortable with their initial counseling sessions, but it’s important that they work with a therapist that they are a good interpersonal match with. If your child is not comfortable with their counselor after several sessions, you may consider looking for another person who is a better personality fit for your child. Another important consideration is what the counselor’s training and qualifications are. It’s imperative to use a counselor who specializes in child counseling so they can apply therapy techniques to a young mind. Since you’re dealing with your child’s mental well-being, don’t hesitate to check references, credentials, and meet with a potential therapist to gauge your comfort level. Often therapists offer free consultations in which they can explain how beneficial counseling will be for your child

Parents can help their children with the school year transition through considering the following points:

- Communicate.

The most important tool for easing the back-to-school transition and helping children manage their stress is communication. Keeping an open channel of parent-child communication is key. Children should feel free to talk about their hopes and their disappointments, their successes and failures, their joys and their anxieties, all with the confidence that their parents can handle whatever they hear and will respond without undue anxiety or reproach. Accept whatever your children are feeling and then move on to helping them learn how to cope. Remember also that such communication should not be a one-time event, but rather on ongoing conversation. - Anticipate.

Communication about the start of the school year should begin before the event itself. Beginning in mid- to late-August, parents should begin the conversation about the beginning of school and its possible stresses by asking their children about what they anticipate in the coming year…academically, socially, and in terms of athletics, dance or other extra-curricular activities. In their own words, parents might ask their children what they hope for and is there anything that they fear? What are they looking forward to and what do they worry about? - Age Matters.

How we talk with our children and what they hope for and fear differs greatly by their ages. We ask simpler questions and expect to be more active in helping young children cope. We are careful to emphasize strengths and not to be intrusive with our early teens. However, we can be more direct and appreciate the considerable capabilities of our 16 to 18 year olds. - Complexity Matters.

We must also consider the complexity of our children’s school experience. They face not only academic challenges and accomplishments but also complex social relationships, both with peers, adult teachers and administrators. Our children see ample examples of kindness and caring in school, but also copious amounts of meanness and bullying. They are called on to perform publicly, day in and day out, reading, doing math, taking part in class debates, and in gym class. Our children face a complex cultural landscape as well as they join classmates of different races, ethnicities, and religions, some native born and some immigrant, some homosexual and some heterosexual, all in a nation-wide political context that emphasizes division and recrimination. Parents should take an active role in learning about the many roles and relationships their children are involved in at school and offer to help them navigate any complexities that arise. - Normalize.

When Appropriate. The beginnings of new experiences are often hard, at school, at work, in relationships, and in community activities. It is normal for children to have fears and it is normal for transitions to be rough. Letting our children know that this is so and that we have faith in their ability to cope is a good foundation for subsequent action. - Coping Rather than Protection.

Many parents understandably have the desire to solve their children’s problems, to make it all better. However, this does not take full advantage of the opportunity that helping with school transitions offers. It is better to have a conversation with our children about how they can cope, how they can manage the academic challenges and the social strains, than to take care of these issues ourselves. Coaching our children on how to cope will bring benefits that last far longer than solving their problems for them. - Coping Tool Box.

One way to talk with your child about how he or she can cope is to conceptualize this as a coping toolbox. You can discuss both what tools he or she already has, such as reaching out to an adult, and methods that are new to them, such as using calming thoughts or remembering times when they have been successful. - Teachers Are Our Allies.

Finally, I encourage parents to remember that teachers care about our children’s well-being nearly as much as we parents do. Reaching out and talking with our children’s teachers’ – letting them know how our children are feeling, listening to the teachers’ perspective, and enlisting their help when appropriate, goes a long way both to solving problems and letting our children know that many people care about them.

What is Child Therapy/Child Counseling?

Child therapy (also called child counseling) is much the same as therapy and counseling for adults: it offers them a safe space and an empathetic ear while providing tools to bring about change in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

Child therapy (also called child counseling) is much the same as therapy and counseling for adults: it offers them a safe space and an empathetic ear while providing tools to bring about change in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.  Just like adult clients, child clients receive emotional and goal support in their sessions. They may focus on resolving conflict, understanding their own thoughts and feelings, or on coming up with new solutions to problems.

Just like adult clients, child clients receive emotional and goal support in their sessions. They may focus on resolving conflict, understanding their own thoughts and feelings, or on coming up with new solutions to problems.

The only big difference between adult therapy and child therapy is the emphasis on breaking down mental illness, trauma, or any other difficult issue the child is dealing with, to ensure children understand what is happening and can make sense of what they are experiencing.

Child therapy can be practiced with one child, a child, and a parent or parents, or even with more than one family. It is often administered by a counselor or therapist who specializes in working with children, and who can offer the parents and/or guardians insights that may not be immediately apparent.

The therapist and client(s) can cover a wide variety of issues and problems in counseling, including:

- Divorce or separation

- Death of a loved one

- Witnessing or experiencing a trauma

- Bullying

- Sexual abuse

- Emotional abuse

- Physical abuse

- Family or child relocation

- Substance abuse or addiction in the family

- Mental illness, like depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder

Whatever the treatment is sought to alleviate or address, it will likely be very forward-oriented (meaning there will be little looking back or digging up the past) and will probably be conducted in a non-verbal manner for a large portion of the time (including play, games, art, etc.).

In addition, the therapy sessions may focus on five important goals on top of any situation-specific goals:

- Building the child’s self-esteem

- Helping to improve the child’s communication skills

- Stimulating healthy, normal development

- Building an appropriate emotional repertoire

- Improving the child’s emotional vocabulary

To summarize, child therapy is quite similar to therapy for adults in terms of the purpose, goals, and problems it can address, but it narrows the focus to issues that young children struggle with and emphasizes a future-oriented perspective, along with including techniques and exercises that are appropriate for the child’s age.

When is Child Therapy Effective?

As noted above, child therapy can be effective for a wide range of issues. If a parent is not sure whether the child needs counseling or not, the list of symptoms below can be a good indicator. If the child is experiencing one or more of these symptoms, coupled with the parent’s concern, it’s probably a good idea to take him or her in for an evaluation.

The following are symptoms that may indicate a problem that child counseling can correct or help with:

- Unwarranted aggression

- Incontinence

- Difficulty adjusting to social situations

- Frequent nightmare and sleep difficulties

- A sudden drop in grades at school

- Persistent worry and anxiety

- Withdrawing from activities they normally enjoy

- Loss of appetite and dramatic weight loss

- Performing obsessive routines like hand washing

- Expressing thoughts of suicide

- Talking about voices they hear in their head

- Social isolation and wanting to be alone

- Alcohol or drug use

- Increased physical complaints despite a normal, healthy physician’s report

- Self-harm such as cutting.

In addition to these issues, the child may be dealing with:

- Persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness

- Constant anger and a tendency to overreact to situations

- Preoccupation with physical illness or their own appearance

- An inability to concentrate, think clearly or make decisions

- An inability to sit still

- Dieting excessively or bringing followed by vomiting or taking laxatives

If parents decide to bring their child to therapy, they should be sure to stay engaged throughout the therapy process. Child & Adolescent Psychiatry suggests asking the therapist or counselor the following questions:

- Why is psychotherapy being recommended?

- What results can I expect?

- How long will my child be involved in therapy?

- How frequently will the doctor see my child?

- Will the doctor be meeting with just my child or with the entire family?

- How much do psychotherapy sessions cost?

- How will we (the parents) be informed about our child’s progress and how can we help?

- How soon can we expect to see some changes?

Similarly, there are some suggestions on how to talk to a child about going to counseling. It can be awkward or uncomfortable for both the parent(s) and the child to talk about mental health treatment, but following these tips can help them get through it:

- Find a good time to talk and assure them that they are not in trouble. Listen actively.

- Take your child’s concerns, experiences, and emotions seriously

- Try to be open, authentic, and relaxed.

- Talk about how common the issues they are experiencing may be.

- Explain that the role of a therapist is to provide help and support.

- Explain that a confidentiality agreement can be negotiated so children—especially adolescents—have a safe space to share details privately while acknowledging that you will be alerted if there are any threats to their safety

There are many effective forms of child therapy with evidence to back them up, including Applied Behavior Analysis, Behavior Therapy, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Cognitive Therapy, Family Therapy, Interpersonal Psychotherapy, and Organization Training. Younger children may also benefit from Play Therapy, and older adolescents may benefit from Dialectical Behavior Therapy, Group Therapy, or Psychodynamic Psychotherapy,

These therapies may be administered on their own, in combination with other therapies, or as a hodge-podge of techniques and exercises from several different types of therapies. In addition, it may or may not be accompanied by medication, depending on the situation.

One of these therapies may work for a child far better than the others, and the type chosen will depend on the issue(s) the child and family are dealing with. However, like with any form of therapy, it is most effective when everyone involved is on board, supportive, and actively contributing to success.

How an Emotional Child Can Benefit from Kids Therapy

An overly emotional child (or one that struggles with inappropriate emotional expression or emotional dysregulation) may suffer from one or more of a variety of issues, including ADHD, mental illness, anxiety, or even an autism spectrum disorder. Whatever the issue they are facing, child therapy can help them deal with it.

Cognitive therapy is a good choice for emotional children, as it involves reducing anxiety and learning new ideas and new ways to channel the child’s feelings and energy. It will also help him or her to identify their inner thoughts, and try to replace the bad ones with more positive, helpful ones. Applied behavior analysis can help the child learn how to respond to situations in better, more effective ways, and will teach them about rewards and punishments for their behavior. Play therapy is a good choice for younger children with emotional issues since they can act them out through toys or dolls.

The type of therapy and techniques that will work best for the child may also depend on which stage of development they are in; Erik Erikson’s groundbreaking theory on the eight stages of psychosocial development is a commonly recognized and accepted theory and can help differentiate between normal, age-appropriate issues and more troublesome symptoms.

The eight stages are:

-

- Infancy:Trust vs Mistrust. In this stage, infants require a great deal of attention and comfort from their parents, leading them to develop their first sense of trust.

- Early Childhood:Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt. Toddlers and very young children are beginning to assert their independence and develop their unique personality, making tantrums and defiance common.

- Preschool Years Initiative vs. Guilt. Children at this stage begin learning about social roles and norms; their imagination will take off at this point, and the defiance and tantrums of the previous stage will likely continue. The way trusted adults interact with the child will encourage him or her to act independently or to develop a sense of guilt about any inappropriate actions.

- School Age: Industry (Competence) vs. Inferiority. At this stage, the child is building important relationships with peers and is likely beginning to feel the pressure of academic performance; mental health issues may begin at this stage, including depression, anxiety, ADHD, and other problems.

- Adolescence: Identity vs. Role Confusion. The adolescent is reaching new heights of independence and is beginning to experiment and put together his or her identity. Problems with communication and sudden emotional and physical changes are common at this stage.

The final three stages are not relevant for the purposes of discussing child therapy, but they are listed here if you’re curious:

- Young Adulthood: Love – Intimacy vs. Isolation

- Middle Adulthood: Care – Generativity vs. Stagnation

- Late Adulthood: Ego Integrity vs. Despair

Based on these life stages, we know that it is common for children in early childhood to throw tantrums when they don’t get their way; tantrums alone aren’t reason enough to seek a therapist! However, if someone of school age is still throwing tantrums, it may be time to explore therapy and counseling options.

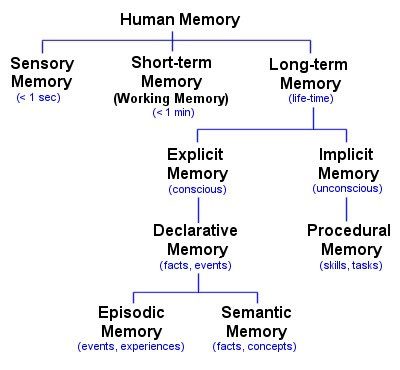

Memory Development Services

Memory Development Services

11 Ways To Strengthen Memory In A Child With Special Needs

Most people don’t think about the process of remembering until they experience memory loss.

-

- But what if the ability to hold and retrieve memories was never there?

- How do you live life like that?

- How do you learn?

Deficits in short-term memory, long-term memory and memory retrieval are common with neurological conditions such as traumatic brain injury, epilepsy, autism, cognitive impairment and learning disabilities. No two brains are exactly alike, so medical studies have had inconsistent results in identifying memory patterns across these conditions.But what if the ability to hold and retrieve memories was never there?

Brain Development

These are the 11 most useful methods.

-

- Use Procedural Memory Whenever Possible For individuals with cognitive impairment or memory loss. The cornerstone of this program is the use of procedural memory, a type of long-term memory that helps people remember how to do each step of a process. In most cases, procedural memory is more reliable than short-term memory or memories that include emotions.

To teach everything from long division and reading comprehension to self-care and chores. Instead of introducing these tasks as concepts, model of each step and increase the level of participation until the subject is able to do it independently. For example, the subject usually does not understand what he/she is reading, but he/she knows that he/she can take a list of questions and go back through a text to find the answers. And even though he/she may not understand a math problem at first, he can line up the numbers and work out the correct answer, then go back to the problem and apply that answer to the original question. - Make A Schedule: A schedule with words, symbols or pictures is an easy way to develop procedural memory for people of all ages. Daily habits and journaling can compensate for many types of memory impairments.

- Take Lots of Photos: Episodic memory is the feeling of remembering one’s own personal history. This type of memory is what allows us to learn from past experience and predict future events. Most people do not fully develop this sense of “autobiography” until they are at least 5 years old – but with a neurological condition, it takes much longer.we take lots and lots of photos to document our autobiographies. Photograph special occasions and everyday occurrences, happy and sad. We name people, places, dates and events. We turn them into greeting cards and theme-based scrapbooks such as “Nature Walks 2010-2012” and “Roller Coasters 2005-2011.”

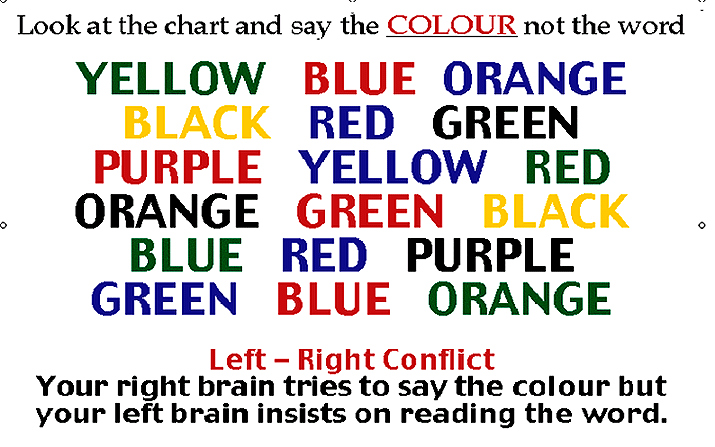

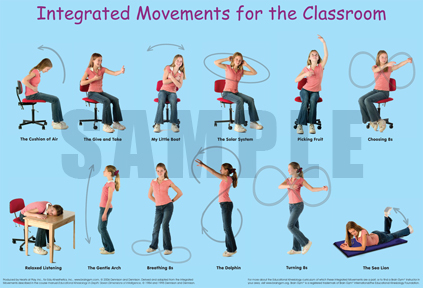

- Exercise: Vigorous daily exercise has been demonstrated repeatedly in published medical studies to improve cognitive function and memory. At home try to incorporate cross-lateral exercise into our daily routine to strengthen connections between the left and right sides of the brain. Get moving with yoga, Brain Gym, Bal-A-Vis-X, swimming and bicycling.

- Relax: The stress hormone cortisol is known to alter memories, so relaxation is an important component to maintaining the integrity of memory. Meditation and regular spiritual practice are excellent tools for supporting cognitive wellness.

- Vitamins: Some types of nutrient deficiencies may contribute to memory loss. After consulting with my son’s pediatrician, I started giving him vitamin B-12 and the antioxidant coenzyme Q10. Other nutritional supplements that may help with memory are omega-3 fatty acids and the antioxidants beta-carotene, vitamin C and vitamin E

- Sensory Input: To understand what children is thinking, often follow his/her eyes so that we can see what he/she is seeing, and we watch his/her face for reactions to changes in the sensory environment. We’ve noticed that sounds, smells, colors and textures can cause a forgotten memory to raise to the surface of his/her mind. A few bars of a song will remind of the last time he/she heard that music, and a smell will remind him/her of another place with that same smell. He/she is much more likely to remember something that has a sensory experience attached to it.

- Creative Output: Having a creative outlet such as writing, photography, painting, sculpture, woodworking or jewelry making tends to reduce stress and increase memory retrieval. Make creativity part of the daily routine!

- Repetition Through Stories: Used stories to help children process events. To ask them to state both facts and emotions in each story – he/she has a thick collection of stories now. He/she reads and re-reads, writes and re-writes each one.

- Keep It Simple: Simple concepts are much easier to remember than complex concepts. Break down large ideas into smaller chunks that can be stored in long-term memory.

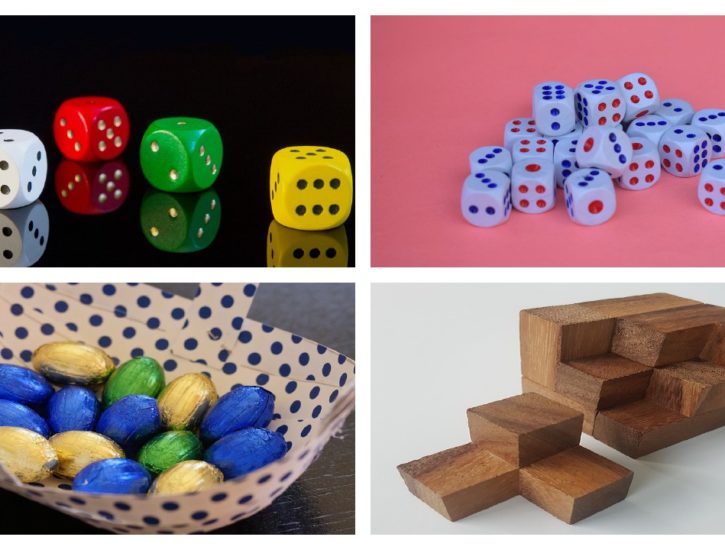

- Make It A Game:Memory games and exercises have been around for centuries because they really work. A game does not have to be complicated or expensive – it can be as simple as a treasure hunt or I Spy at home – but it should always be fun!

- Use Procedural Memory Whenever Possible For individuals with cognitive impairment or memory loss. The cornerstone of this program is the use of procedural memory, a type of long-term memory that helps people remember how to do each step of a process. In most cases, procedural memory is more reliable than short-term memory or memories that include emotions.

Brain Gym Exercises

Brain Gym Exercises

What Are Brain Gym Exercises?

Brain gym exercises are simple tasks that help to stimulate brain activity and keep the mind engaged. Just like when you exercise you engage and strengthen core muscles, brain exercises stimulate blood flow to the brain and increase oxygen supply to the brain. Brain gym exercises release stress, enhance learning and development while effectively engaging the brain. Not only younger kids, but even older kids and adults can benefit from these effective yet simple brain gym exercises. And that will help the child develop good motor skills, memory and ensure effective brain Development.

Top 10 Brain Gym Exercises

- Cross Crawl:Cross crawl is a simple exercise that can be done while sitting or standing. Ask the child to touch his left elbow to his right knee and then right elbow to his left knee. This exercise is most effective when done slowly. Cross crawls helps with the bilateral integration of the left and right brain and also energizes the body.

- Number 8:This is one of the simplest brain exercises for your kid but effective nonetheless. Ask your child to draw number 8 on a book or a piece of paper repeatedly. It should be drawn with a loose hand and freely. Drawing this figure relaxes the mind and loosens up tense muscles.

- Draw with the other hand:Another simpler brain exercise is to ask the child to draw with his non dominant hand. If the child is right handed ask him to draw with his left and if the child is left handed ask him to draw with his right. Remember this has to be a fun activity so let the child draw whatever he wants and however he can.

- Brain Buttons:Ask the child to lightly press his head (between the hairline and the eyebrows) and then close their eyes and breathe. You can instruct the child to breathe in deeply and then breathe out. In between also ask the child to take a 5 second pause and then breathe in deeply. This is a rejuvenating exercise that even adults can do occasionally.

- Hook ups:For hook ups ask the child to sit in a comfortable position and then ask him to cross left ankle over his right. Stretch the arms and cross them and interlace the fingers. Then ask the child to bring his hand to his chest and keep still and breathe deeply for a minute. Hooks up help the nervous system to calm down and relax.

- Memory games:Simple games like memory games can serve as an effective brain exercise. You can bring out all the toys your kids have lay them on the floor, ask the child to close his eyes and remove a couple toys and ask the child to find out which toy is missing. This will stimulate memory function and brain activity.

- Board Games:Board games such as checkers, monopoly etc can be quite stimulating as well. You can bring out the good old ludo, carom or even the chess board can play with the kids. A competitive atmosphere and a challenging game can be a great brain gym exercise for all the members of the family, kids included.

- Scissor jumps:Jumping exercise are quite effective to promote brain functions. If you have access to a trampoline ask your kid to jump on it and while jumping ask him to cross his arms and legs. You can even do it without a trampoline just ask your kids to jump a little higher. This exercise promotes sensory development and good motor skills.

- Puzzles:Another great exercise would be to solve puzzles. Buy a puzzle that is suitable for your child’s age and sit down with the kid and help him or her solve it. It could be as simple as matching objects and as tricky as creating a picture. Choose the puzzle appropriate for your child’s age, do not tax the child buy undertaking difficult puzzles.

- Nesting and block pattern toys:Nesting toys and building blocks are easily available in the market. Encourage your child to build block patterns like making a pyramid or a cubicle this will stimulate their brain and encourage to come up with different patterns on their own. You can also buy come nesting toys that fit inside each other, dismantle them and ask the child to put it back together. This might look simple but is an excellent exercise for kids.